Tappets Explained, Part 2

In part 1, we talked about what tappets do and got a little sidetracked on adjustable pushrods because they relate to how tappets fit into the grand scheme of the Harley-Davidson valve train. Now, we’ll focus on how hydraulic tappets actually work.

As we mentioned previously, tappets translate the eccentric profile of the cam lobes into an up-and-down motion that opens the valves and allows them to close. They also provide a way to minimize the free lash between all components of the valve train: pushrods, rocker arms, and valves. Eliminating lash in the valve train and keeping it quiet are what really sets hydraulic tappets apart from solids.

With solid lifters, the pushrods or tappets are manually adjusted to zero lash on a cold engine. As the cylinders heat up and grow in length, due to thermal expansion, a certain amount of lash develops, and the valve train gets noisy. That’s just how it is. Solid lifters are pretty foolproof, but they’re noisy. Hydraulic tappets need to be set up initially, if adjustable pushrods are installed, but after that they are self-adjusting.

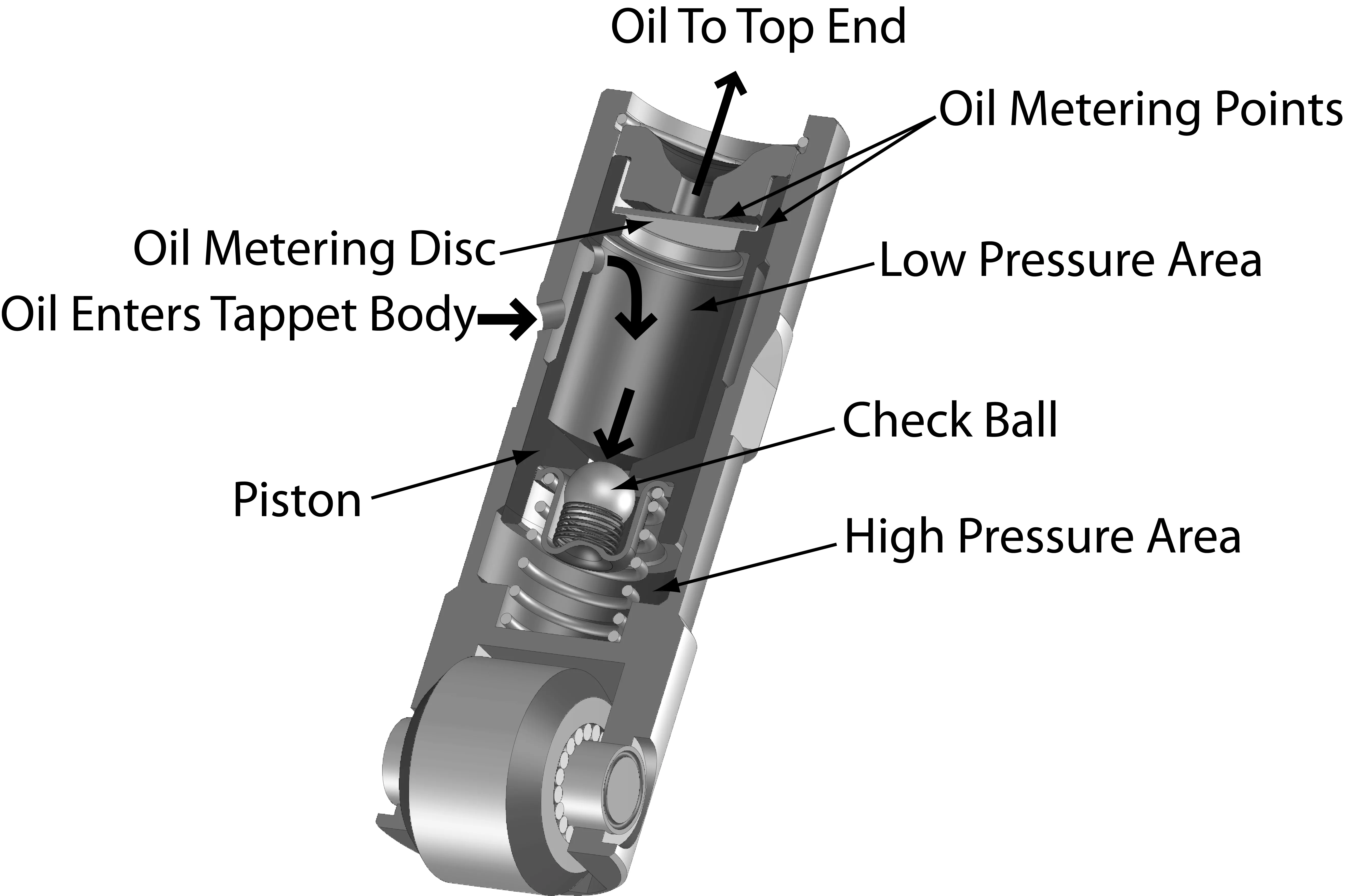

A picture is worth a thousand words. This cutaway view of an S&S Premium Hydraulic Tappet for 1999–later Harley-Davidson big twin and ’00–later Sportster models shows what’s inside. The thick arrows indicate oil flow. See the body of the article for a description of what’s going on.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

The Inside Story

A modern hydraulic tappet is basically a cylinder with a valve and piston arrangement inside (see illustration). On top of the piston is a cupped insert that holds the lower ball end of the pushrod.

Oil enters the tappet body and flows into a groove around the piston that directs oil to the oil-feed hole in the piston. Oil enters the piston, flowing into a chamber that we call the low-pressure area. When the tappet is on the base circle of the cam, the valve is closed. No force is being exerted on the tappet by the pushrod, and oil pressure from the oil pump pushes oil down past the check ball (some tappets have a reed valve) to what is called the high-pressure area beneath the piston. When the cam starts pushing the tappet upward against the force of the valve spring, the piston puts pressure on the oil beneath it in the high-pressure area. This pressure closes the check ball, trapping the oil beneath the piston. The trapped oil will not allow the piston to move, so the piston pushes the pushrod upward to open the valve.

No matter how close the fit between the piston and tappet body, a very small amount of oil will leak past. When the tappet is once again at the base circle of the cam, any oil that might have escaped will be replaced, and if there is any lash in the valve train, additional oil will flow past the check ball to fill the gap. As a result, the piston moves upward in the tappet body to take up the slack. This is how a lifter “pumps up.” It doesn’t happen just once; it’s happening continuously, as long as the engine is running and there is oil pressure available. That’s how hydraulic tappets automatically compensate as cylinders grow in length from thermal expansion.

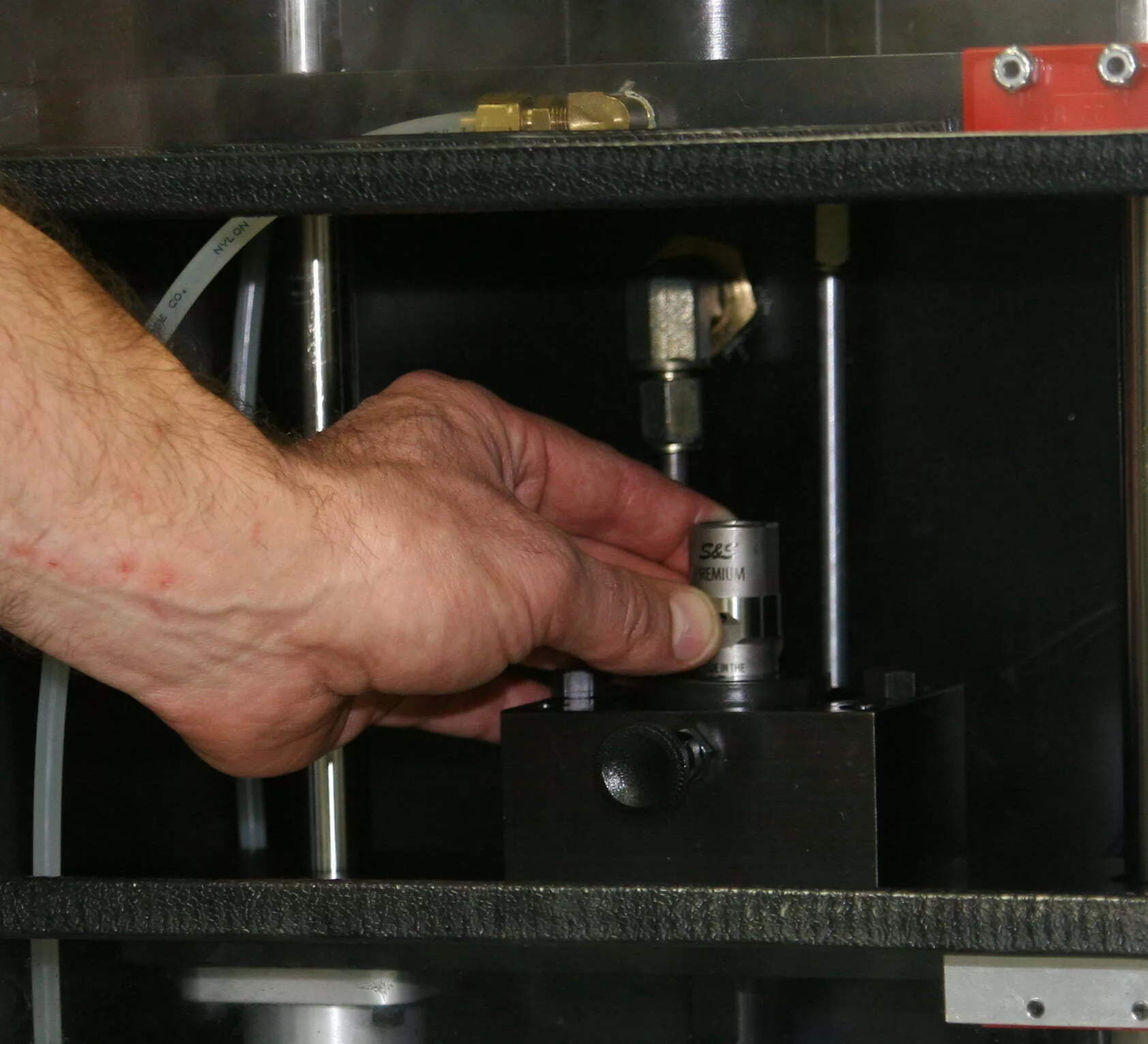

An S&S technician places an S&S Premium Hydraulic Tappet in a specially built leak-down tester to verify that it has been machined and assembled correctly, so it will perform as promised when you put it in your engine.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

Alert readers will probably be wondering why this hydraulic piston doesn’t just keep pumping up until it pushes the valves open. Here’s why: If a point is reached where the pushrods are always exerting force on the tappet, the oil beneath the piston will always be under pressure, keeping the check ball closed. No more oil will get in, so it won’t continue to pump up.

Beginning with 1984 big twins, tappets also have another function: providing a metered supply of oil to the top end of the engine. The cup in the top of the tappet has a hole in the center that feeds oil through the pushrod, which is hollow, up to the rocker arm. Top end oil is metered by a disk just underneath the cup in the tappet, and it’s pretty much just a controlled leak. It’s a very precise leak due to close machining tolerances and continuous testing.

The tappet on the left fits ’84–’99 Harley-Davidson Evolution big twin and Sportster engines. This tappet style was the first in the Harley-Davidson lineup that supplied oil to the top end through the pushrods. The tappet on the right fits ’99–later big-twin models and also feeds the top end oil through the pushrods. Note the smaller-diameter roller.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

S&S has been manufacturing tappets in-house for a while now and last year introduced a line of premium tappets. Our premium tappets are machined to very close tolerances but still have to pass an end-of-the-line leak-down test to ensure that they will pump up quickly. In addition, they contain a low-mass, bearing-grade silicon nitride check ball and an optimized check ball spring for quicker valving action. That equates to faster pump up and the ability to handle increased spring force from high-lift cams and performance valve springs at higher rpm.

The inner workings of hydraulic tappets are pretty complicated, and it can give you a headache thinking about it. What you really have to understand and take away from this is that hydraulic tappets are for the most part self-adjusting. After an initial setup, you don’t have to worry about them. And that’s a good thing!