Tappets Explained Part 1 | Tech Tips

When S&S Cycle opened its doors back in 1958, the first product offered for sale was a solid lifter conversion kit that allowed performance-minded riders to get rid of the troublesome hydraulic units of the day. So if the first product S&S produced allowed performance enthusiasts to get rid of hydraulic tappets (a.k.a. lifters, cam followers, etc.), why are we even talking about them now? Well, that was 55 years ago, and the tappets we have now are a lot better than the ones George J. Smith was eliminating in 1958. Those old lifters were prone to collapse at high rpm, serving as a built-in mechanical rev limiter. If your valve train fails at a certain rpm, it doesn’t matter what other goodies you have in your engine. That’s as fast as your engine is going to turn. Period.

So what are tappets, and what do they do? A tappet is a device that slides or rolls on the cam lobe following the cam profile and translates the eccentric shape of the cam lobe to an up-and-down motion that opens and closes the valves. Harley-Davidson engines use roller tappets, which means they have a small wheel on the lower end that rolls on the cam as it turns. Tappets also provide a way to take up the lash between all the various components in the valve train. Hydraulic tappets contain a hydraulic piston that moves to automatically compensate for engine height growth from thermal expansion, keeping the valve train lash at zero.

This historic S&S ad for pushrods from the early ’60s illustrates how long S&S has been selling pushrods for Harley-Davidson motorcycles. These pushrod kits were the first products S&S offered in 1958. Pushrods and other valve train components, such as high-performance tappets, are still a vital part of any high-performance engine upgrade to extend the effective rpm range of the engine, enabling it to make more power.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

Pushrod adjustment is a very frequent topic of phone calls to the S&S tech department. Like most things, it’s pretty simple when you understand it, but with the amount of myth, urban legend, advice from the end of the bar, and plain B.S. floating around, it’s kind of hard to sort out the facts.

The Facts

In order to adjust a hydraulic tappet, you must use an adjustable pushrod. Stock engines don’t have adjustable pushrods since the factory relies on the self-adjusting feature of the hydraulic tappets to compensate for any machining tolerances in the construction of the engine as well as thermal expansion. It works just fine in that kind of narrowly defined application, but for a performance engine, adjustable pushrods are pretty handy. They can adjust for cams with non-stock base circles, decked heads, shortened cylinders, special valve jobs, roller rocker arms, and a host of other performance modifications that can affect the valve train.

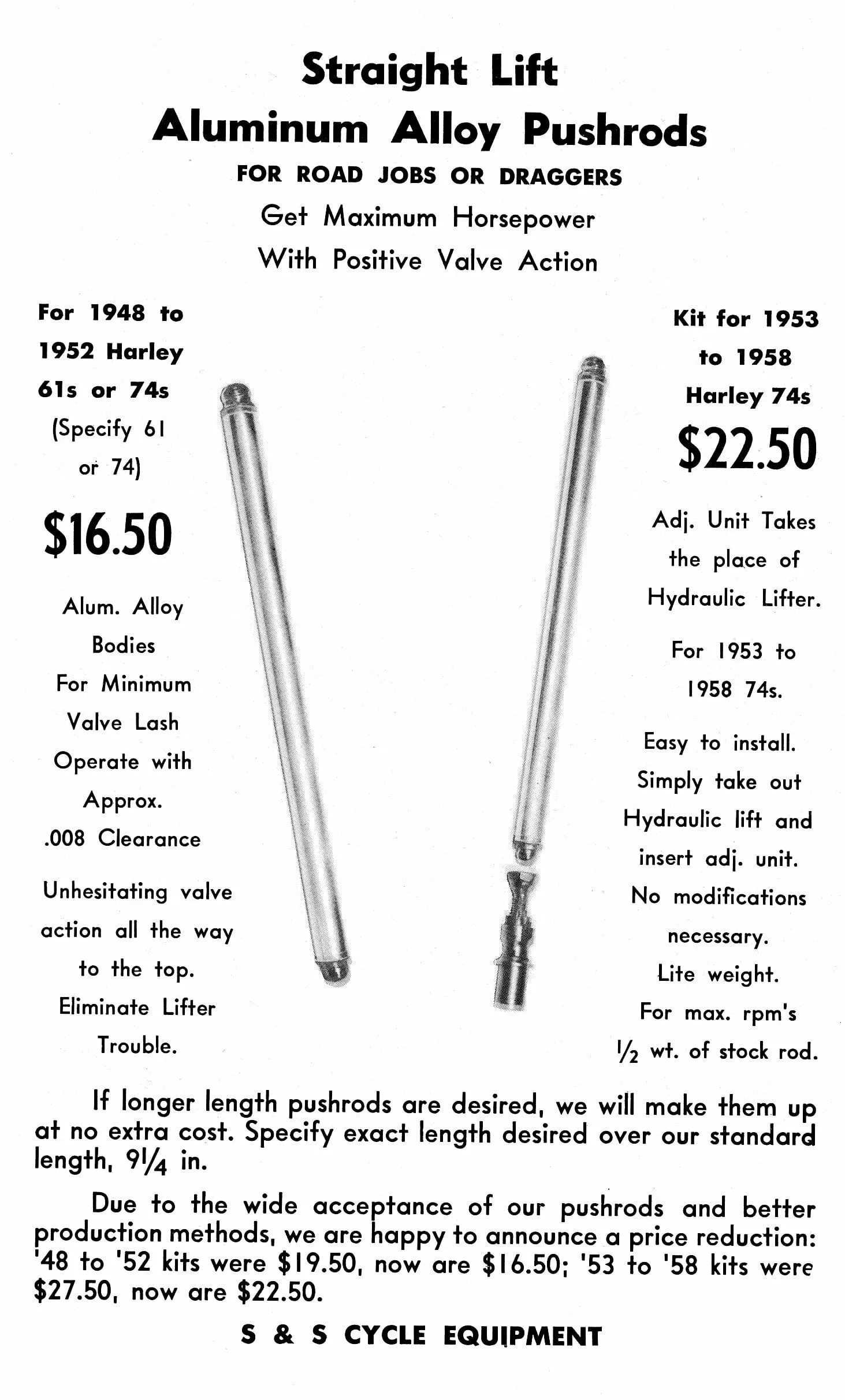

This illustration shows the relationship between cam lobes and tappets on a rear gear drive cam as viewed from the cam side of a ’99–later big-twin engine. As you may be aware, in a gear drive setup, the rear cam turns in the opposite direction of the crank and front cam. The intake tappet (A) is just starting to roll down the backside of the cam lobe, closing the intake valve. The exhaust tappet (B) is already on the heel, or base circle, of the cam so the exhaust valve is closed. Tappets translate the shape of the cam lobe into up-and-down movement to open and close the valves.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

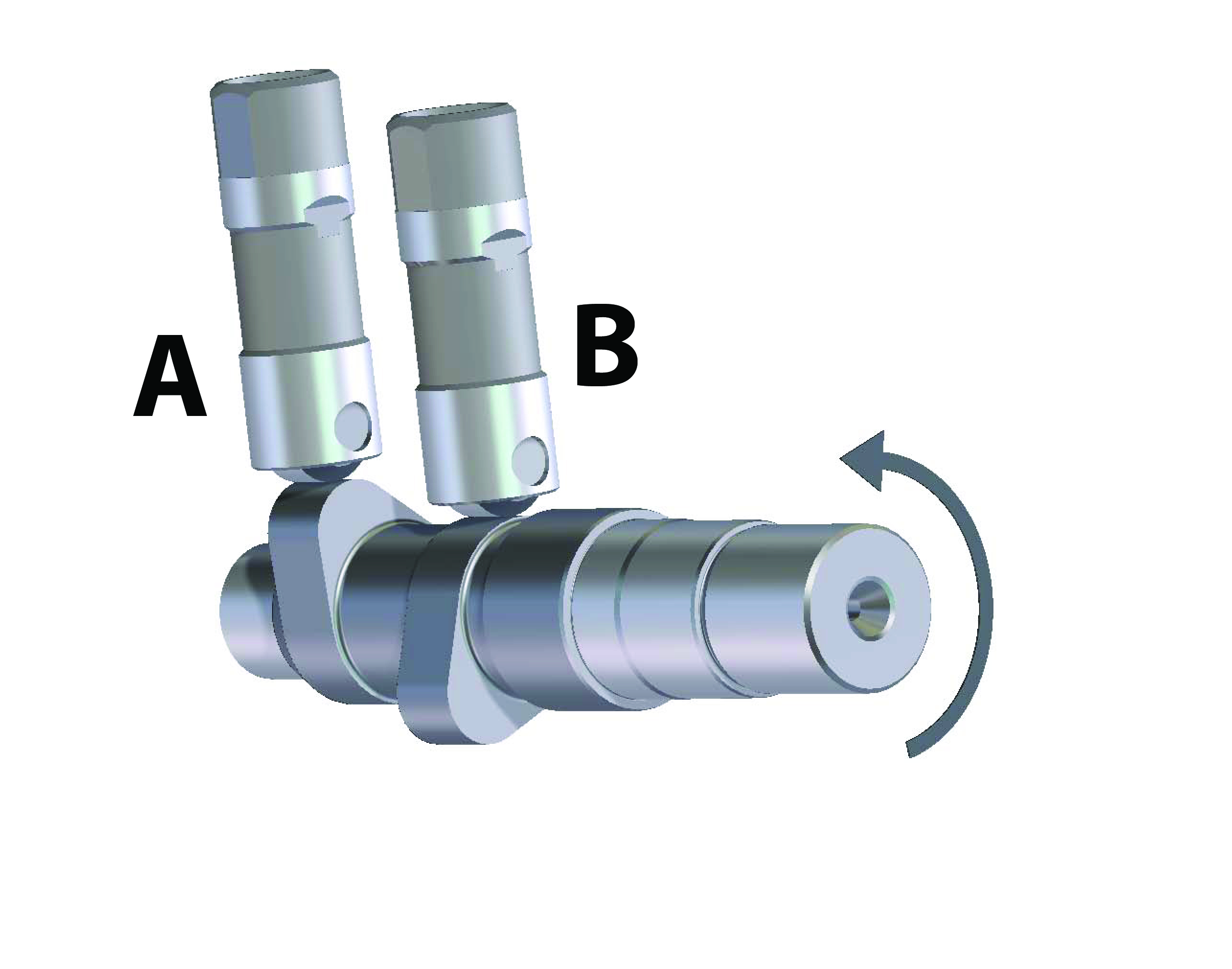

You start with a cold engine, pull out the spark plugs, and roll the engine over slowly until both tappets for one cylinder are at the lowest point of their travel. The valves should be closed at that point. The pushrod-adjusting screw is turned, shortening the pushrod, until it no longer touches the cup in the top of the tappet. That allows the piston in the tappet to rise to its highest position. Then the pushrod is lengthened until the ball-end just touches the cup. You should just be able to turn the pushrod between the fingers with no shake or rattle—just a little roll. The pushrod is then lengthened in order to push the hydraulic piston in the tappet to the approximate center of its 0.2-inch available travel. The number of turns can vary according to the thread pitch of the adjuster screw. S&S pushrods have 32 threads per inch, so we recommend four turns (or 24 flats) of the adjuster nut. Once the locking nuts are tightened, you have to wait about 10 minutes for the oil to bleed out of the tappets. If the engine is turned over before the tappets have bled down, the valves will not be fully closed and could hit each other. You don’t want that to happen. If the pushrods are loose enough to be turned between your fingers (valves fully closed) after 10 minutes, you can turn the engine over until the tappets on the other cylinder are at their lowest point of travel and adjust them the same way. Pretty simple, really.

The procedure for adjusting pushrods with hydraulic tappets is the same for nearly any engine, whether it is a Harley-Davidson Evolution powerplant (shown here) or a Twin Cam 88, a 96, a 103, or the engine in a Sportster model. It is important to follow the pushrod manufacturer’s instructions, as the number of turns required in the adjustment procedure might vary with the thread pitch of the adjusters. S&S Quickee (shown) and S&S standard adjustable pushrods have 32-threads-per-inch adjusting screws and require four turns (or 24 flats) of the adjuster.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

Sometimes during a tech call about tappet adjustment, “car guys” will ask, “But where do I stick my feeler gauge?” Being as polite as we are, we rarely tell them where to stick it. We just tell them we don’t use feeler gauges.

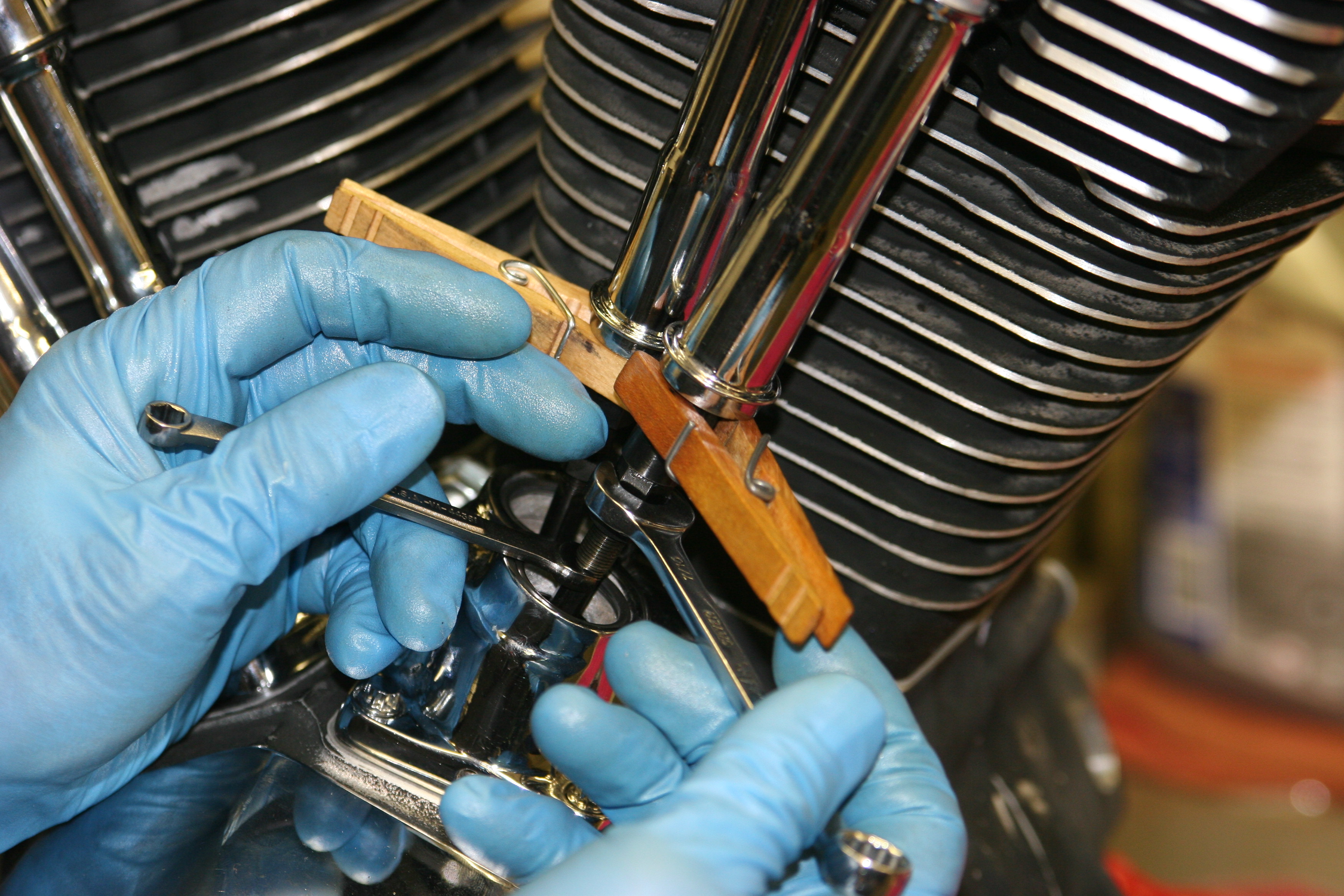

This photo shows the difference between tappets for Harley-Davidson Evolution big-twin engines and 1999–later big twins with Twin Cam 88 and larger engines. The tappet for the Evolution engine on the left has a larger-diameter roller, and the design is quite a bit different. The tappet in Evolution engines is held in alignment with the cam by the slots in the bottom of the tappet guide, while tappets in the later engines have a flat side on top and are aligned with a dowel in the tappet bore. The 1999–later big twins and 2000–later Sportster models use the same tappets.

Courtesy of S&S Cycle

We’ve covered what hydraulic tappets are, what they do, and how they’re adjusted. Next, we’ll delve into what’s inside them that actually makes them work.