Scout’s Honor

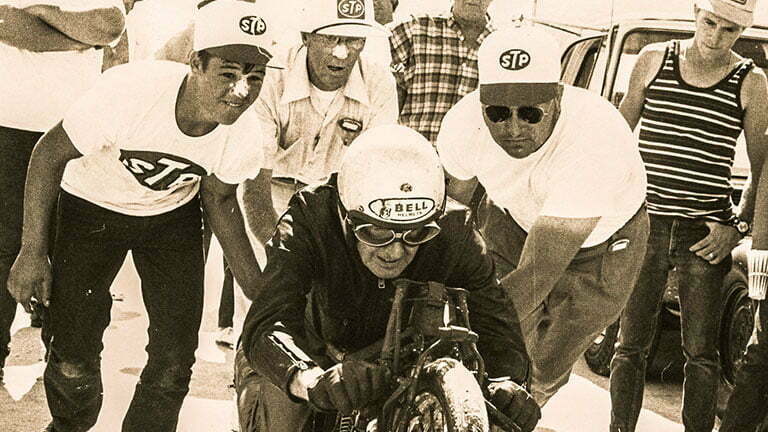

Burt Munro at the salt.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

Not surprisingly, the 1911 Senior TT race, held for the first time over the Isle of Man’s Snaefell mountain circuit, was won by local talent. Britons Oliver Godfrey, Charles B. Franklin, and Arthur Moorhouse took first, second, and third. On American motorcycles.

Specifically, Indian motorcycles. Up until then, most Brit iron had single gearing (if any) and belt drives. The Yankee steeds from across the pond, on the other hand, sported a countershaft gearbox and chain drive, technical innovations that gave Indian jockeys a serious advantage on the hilly course.

Unlike Harley-Davidson, Indian started at the racetrack and moved to the road, not vice versa. Indian’s founding parents, George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom were veteran bicycle racing guys. When they met at Madison Square Garden in December of 1900, Hendee already wanted to make motor-driven iron. The idea of a simple, practical consumer motorcycle stewed in his noggin. Hedstrom’s De Dion-powered pacer bikes brought that brain soup to full boil. Indian was born from their agreement, signed in pencil on an envelope.

Hedstrom spent that winter banking sweat equity into a prototype at his Connecticut workshop. In early 1901, he took it to Hendee in Springfield, and the company was up and running later that year. A year later, Indians were making a name for themselves at the first motorcycle endurance race in the United States.

Held July 4 and 5, the race route took competitors from Boston to New York. Three Indian bikes not only competed, but all of them turned in perfect scores while running up to 40 mph. Just to put that in perspective, try mounting a single-cylinder lawn mower engine into a bicycle frame with rigid forks. Now ride it for two days on crappy roads. When you’re done shaking and aching, feel free to email us with the details of your experience.

Like Harley, Indian’s founders put their money where their motors were. George Hendee raced the second enduro a year later—only this one was more grueling. Enduro II: The Wrath of Bumpy Roads (or whatever it was actually called) went from New York to Springfield and back over a three-day period. Not only did Indian’s president race himself, but he had the audacity to win the thing. Two months after that, George Holden claimed another Indian win when he rode his Indian to victory at New York’s Brighton Beach dirt track. Holden rode the 150-mile race in four hours. All aboard a primitive iron single set in a rigid bicycle frame.

Track lessons weren’t lost on chief designer Oscar Hedstrom. No one likes having their bladder shaken until their urine fizzes like Coke and Mentos; it was time to smooth out the ride. Three years after the first Indian raced that first enduro, Hedstrom evolved the OG Indian into a better beast with an engine-shaft shock absorber, steel cylinder, and a sprung front end replacing the old rigid bicycle fork.

Two other upgrades trumped all of those changes, however. That year, 1905, was when Indian introduced its twist grip throttle. Hendstrom’s experimental V-twin motor was the second.

Among the first racers to play with the new V-twin design were long-distance racers George Holden and Louis Mueller. And by “play with” I mean “beat it like it owed them money.” In 1906, they made the 3,500-mile trek from New York to San Francisco in 31 days, 12 hours, and 15 minutes, a record for transcontinental travel back then.

Indian took its act international in 1907 when T.K. Hastings became the first American to enter an American machine in a British motorcycle race. His Indian victory in England’s Thousand Mile Trial (later known as the International Six Days Trials) let the world know Indian meant business and enhanced Indian’s reputation back home. England’s reaction to this wasn’t exactly warm and fuzzy; some motojournalists of the time were outright pissed off. That only makes sense. Back then the US wasn’t the top dog among world powers. That was the British Empire’s gig. For Great Britain to lose any competition to Team USA was the political equivalent of getting your ass handed to you by your younger brother. Some sour grapes were understandable.

Come 1911, Indian fielded full-fledged, in-house motorcycles, on and off the track. Gone were the bicycle frames and Thor-built motors used in the earlier models. Indians were motorcycles built solely for the purpose of, well, motorcycling. The company’s race record in 1911 reflected that. Indian iron took most of the victories at dirt and board tracks alike. Hell, Don Johns turned in an amateur 20-mile record in California with an average speed of 83 mph—27 mph more than the previous amateur board track record of 56 mph held in England.

For Indian, no other month before could hold a candle to July of that year. Volney Davis made his run at a new transcontinental record Stateside. Meanwhile, Oliver Godfrey won the most prestigious motorcycle race in the world at the time, the Isle of Mann TT, followed by Charles Franklin in second place, and A.J. Moorhouse in third, all three astride Indian race bikes.

But wait, there’s more. The next day, 40,000 people gathered in Indy for an Independence Day celebration. One of the day’s festivities was a five-lap President’s Race, where Johnnie Sink and his Flying Merkel faced off head to head against Erwin Baker and his Indian. After Erwin won, he chilled with President Taft in his private box, making national news for the Indian in the process.

Back in the UK, Jake DeRosier challenged England’s Brooklands oval concrete track four days after Baker’s win. See, the British press didn’t think Jake could repeat his record mile run in England. This was his way of proving them wrong. On July 8, DeRosier roared to a mile in 41 seconds, equaling his best time in the United States. However, the UK wasn’t done with him nor he with it. A week later, Jake faced off against England’s Charlie Collier in a best of three series. DeRosier and his Indian took two of three from Collier and his Matchless.

Racing success meant good press, which translated into good sales. In 1911, Indian had racing cred on steroids and crack. Production shot through the roof; 20,000 Indians were made in 1912, 35,000 bikes rolled out of Springfield in 1913, and 1914 was even better. By then, Indian had 2,000 dealers worldwide selling some 60,000 new models fresh off the production line.

That was the good part. The rain on this particular parade came when Hedstrom left the company. One rumor says he and Hendee had a falling out. Regardless, Oscar returned in 1916 after George retired in 1916. In the interim, Hendee brought in Charlie Gustafson to replace Hedstrom. Gustafson preferred a side-valve arrangement over Indian’s inlet-over-exhaust. The new arrangement debuted on the 1916 Powerplus twins.

Erwin G. “Cannonball” Baker earned his nickname aboard one of those new twins. That was the year he shaved the new coast-to-coast riding record down to 11 days, 12 hours, 10 minutes—on a bike he’d only seen three hours before takeoff.

He wasn’t the only guy punishing the new Powerplus twins. The US Army ordered 15 of the Indians to help chase Pancho Villa into Mexico, then bought out Indian’s entire line when the United States entered a little scuffle called World War I.

After the war, Indian’s design team was arguably the strongest it ever had. Led by Oscar Hedstrom, he and Gustafson were joined by the same Charles B. Franklin who’d captured second place at the 1911 Isle of Man TT. Eventually, Franklin became vice president of the company. He also convinced Indian to return to the TT in 1922 and 1923.

All of that pales next to his biggest design contribution, however: the Indian Scout. This new 500cc V-twin continued Indian’s racing dominance throughout the 1920s, into the 1930s, and beyond. Indian introduced the Scout in October 1919 as a 1920 model, with a 606cc motor.

Scout displacement went up to 745cc in 1927 in response to Excelsior’s popular Super X model. Dubbed the Indian 101 Scout, the new bike had more rake, a longer wheelbase, and a lower seat height. It was also the first Scout equipped with a front brake. The 101 Scout had a reputation for superior handling and was extremely popular with hill climbers, racers, and trick riders.

As good as the 101 was it had a really short production life. A minor financial hiccup called the Great Depression forced every motorcycle company in America to shave expenses just to stay alive. For Indian, that meant discontinuing the 101 Scout in 1931 because it cost just as much to make as a Chief, only with a smaller profit margin.

This is where the racing honeymoon ended for Indian. Not that Indian stopped winning. Far from it. Going into the 1930s, Indian was still one of the biggest (if not the biggest) dogs in the yard when it came to competing. Up until the death of the 101 Scout, though, Indian designs kept getting better. Post-mortem, Indian made its first big mistake when it launched the Scout Standard.

While management was busy killing the 101, they also came up with the great idea of a universal frame for the entire model line. Except for some variations in detail, the Scout, Chief, and Four all had the same chassis starting in 1932. It was a good way to reduce costs, but the heavier skeleton translated to Scout riders looking for light weight in a motorcycle. Weight can be death at a racetrack. Anything that adds it isn’t going to go over well with that segment of the rider faithful.

That’s why Indian designed the Sport Scout of 1934. With its lighter frame, girder forks, alloy heads, and upgraded carburetor, it was a huge improvement over the Standard (though still 15 pounds heavier than a 101).

This was the machine that kept Indian dominant at the track and dueled against Harley-Davidson’s racing workhorse, the WR. When Class C racing was born in the 1930s, Indian hit the ground running. The Sport Scout’s practical design made it a natural for the consumer-friendly new racing category. Sport Scouts ate up the competition like Jabba the Hutt at a Hometown Buffet. Victories fell to them on speedways, half-miles, miles, and roadraces all over the country. When Ed Kretz won the first Daytona 200 in 1937, a Sport Scout was the steed that carried him to victory.

Like Harley-Davidson during the later AMF years, Indian’s racers in the 1930s were as successful at the track as the suits in the boardroom were not. Failed ventures into non-motorcycle products ate up profits, leaving less and less money for the consumer technical innovations that were Indian’s hallmark. While Ed Kretz and other Indian champions were winning at the track, Harley-Davidson was eating up Indian’s market share and evolving technologically. The year before Kretz won in Daytona, Harley introduced one of the most iconic V-twins in history: the Knucklehead.

Indian’s cash flow problems followed the company out of the Great Depression and, despite switching over to military production in World War II, into the 1940s. E. Paul DuPont sold Indian to Ralph B. Rogers in 1945. Rogers thought he could save Indian by switching over to making lighter weight motorcycles, which were so popular after the war’s end. Big-twin production dropped off to almost nothing, including that of the aging Sport Scout. In spite of all that, Indian’s wins continued as its devoted group of engineers constantly updated the proven Sport Scout engine in order to stave off the ever-increasing competition from Harley-Davidson and its race-specific WR.

Rogers and Indian’s old guard butted heads over how important racing was to the company’s future. He was skeptical, they felt racing was vital. Compromise came when a reluctant Rogers okayed development of the Model 648 Sport Scout, albeit on a shoestring of a budget. With its big base motor, the 648 may have been the greatest of the Sport Scouts. It enjoyed immediate success, keeping Indian’s infamous Wrecking Crew a force to be reckoned with all the way into the 1950s. In 1948, Indian built just 50 units of the Sport Scout, one of which took racing legend Floyd Emde to victory in that year’s Daytona 200.

As part of the new direction, Indian created the disastrous Laconia Scout. Lighter than either a Sport Scout or anything Harley was racing, the Laconia Scout was a vertical twin, not a V-twin. Only 24 of the Laconia Scouts were made in 1949 (well short of the 50 usually made to qualify a motorcycle as a production machine eligible for racing in Class C). The 440cc vertical-twin motor was an underpowered wuss. Indian’s engineers had the unenviable task of turning shit into gold. They did the best they could, but conditions weren’t exactly optimal. Not only were they saddled with a lousy powerplant for racing, but the whole project was rushed. Still, they did the best they could. By increasing cylinder bore from 2.375-inch to 2.540-inch and keeping the 3-inch stroke, the designers upped displacement from 440cc to 500cc. That in and of itself helped level the playing field somewhat (more displacement, more power).

Vertical twins were pretty new territory for Indian’s racing engineers. Giving them a weak motor and crappy transmission to work with, coupled with a serious time limit, didn’t help. When the Laconia Scout took to the Laconia racecourse on June 19, 1949, Indian got a PR nightmare for its trouble. Come day’s end, at least 11 of the 24 Indian verticals were on the disabled list. Only three placed in the top 20 finishers.

The stress of competition shined an ugly light on the Laconia Scout’s biggest problem: its magnetos. Magneto failure was the leading cause of death for most of the casualties Indian suffered at the track that horrible day. Some people believe the problem was bearing failure, others the coils. Whatever the reason, the magneto had to go.

Provided the damage hadn’t been as extensive as it was. Not to the machines, to the company. June 20 saw a lot of soul searching at the wigwam. Harry Potter couldn’t have hidden the ensuing PR fiasco. Meanwhile, the design team brainstormed solutions on the third floor. Not that any of that mattered.

Two months earlier, Ralph Rogers went to England to secure more money to keep Indian afloat. Part of the deal he made included setting up a distribution company called “The Indian Sales Company.” In exchange for financing, Rogers agreed to let that company import European iron to the US to be sold in association with the Indian name. One of those manufacturers was Norton, whose 500cc Manx International racing bike came to dominate American tracks in the years to follow. With a motorcycle like that, would you go to the time and expense of making a bad design work? Rogers didn’t.

Officially, that spelled the end of the Laconia Scout and Indian racing vertical twins. Unofficially, Indian’s engineers and dealers wouldn’t go so quietly into the night. Working with indie teams and off the clock, both groups of people kept the vertical twin going well after the company gave up on it. Indian’s Wrecking Crew reflected that spirit also. They were kicking ass at the track all the way up until the company went out of business.

And beyond. In 1967, New Zealander Burt Munro chased (and caught) a world land speed record aboard his 1920 Indian Scout. He set his first New Zealand speed record in 1938 and set seven more local records as time went by.

Seeing as how he was racing his Indian almost two decades after the last Scout rolled out of the factory, oh, and doing so from a continent half a world away, constantly modifying his bike for runs at the Bonneville Salt Flats was as trouble-free as walking a greased cable across the Grand Canyon in a windstorm while wearing a sweat suit stuffed with wolverines.

As often as not Burt made his parts and tools himself. He’d cast a lot of the parts on his own and used an old spoke as a micrometer. Cylinders, flywheels, pistons—all of them he made himself. Eventually, he took is old Scout from its original 500cc displacement up to 950 using nothing but trial, error, and guts. All told, he visited the salt 10 times. First for reconnaissance then nine more times to race. He set his first record in ’62, second in ’66, and his final in ’67, at the age of 68. Forty-seven years after he’d first bought that Scout brand new, it was still an ass kicker.

What Munro’s bike really illustrates is just how well made the old Indians were. Whether it was Munro or the Wrecking Crew of ’40s and ’50s or Floyd Emde and Ed Kretz at Daytona, or Oliver Godfrey at the Isle of Man in 1911, Indian racers and their machines were forces to be reckoned with at any race. It’s a huge part of the company’s legacy to motorcycling and one I’m curious to see what a new generation of Indian riders does with the new Scout.

See what those Scouts have been up to at the track.

…or you could just ask Roland Sands. He MIGHT know…

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company