Indian Heritage

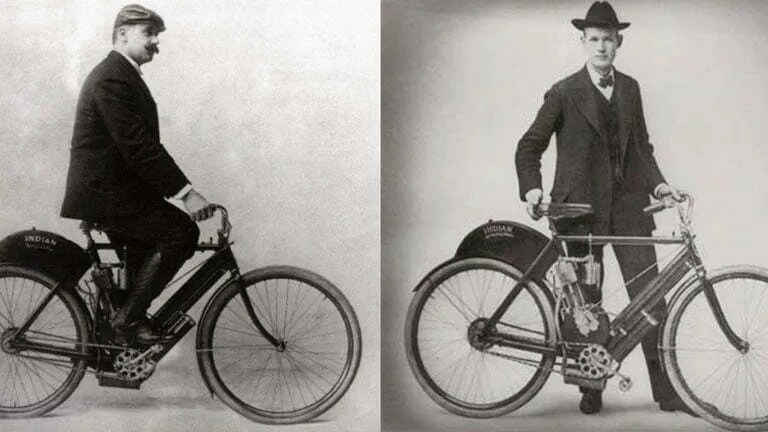

Hendee and Hedstrom, 1902.

Words: Mark Masker Photos: Courtesy of Indian

When Polaris picked up the challenge of bringing Indian back from its latest death, the company made the wise decision of bringing back not just the Indian style but the history that goes with it. Polaris even says so in the press release. What the hell does that mean, though? Most of us know Indian originally went out of business in 1953, Anthony Hopkins played Indian salt racer Burt Munro in The World’s Fastest Indian, and the old Indian Chiefs had big, swoopy fenders. None of which pays full justice to one of the most iconic bike makers of the early 20th century or the dramatic role it played in shaping the world of motorcycling. Polaris took the time to learn all about Indian’s heritage and built that into its new Indian models. While one article ain’t big enough to cover the Indian saga in high-definition detail, we can give you a pretty good thumbnail sketch.

From the get-go Indian was into racing. Hell, the company was practically founded on it. Just not competitions of the motorcycle variety. Indian, like Harley-Davidson, originated from the world of bicycling. The difference being Indian came about from the desire to make bicycle racing better.

One of the earliest uses for motorcycles was as pacers for bicycle races. In the late 1890s, pacers had all the reliability of a Magic 8 Ball, though. Some racing promoters had as many as five to seven pace bikes just to make sure they could run a complete race. That’s where Indian co-founder Oscar Hedstrom entered the picture.

Hedstrom was a Swedish immigrant who apprenticed himself to a watch-making company in 1886 at the age of 16. That’s where he cut his teeth and made his bones as a machinist. Armed with his new skill set, he got his greasy little mitts on the same French De Dion motor found in some motorcycles of the time. By 1901, he’d not only learned the ins and outs of making pacer motorcycles for bicycle races, but he’d actually improved them.

Hedstrom’s pacers were so reliable and easy to ride that in 1900, bicycle manufacturer and race arena owner George Hendee came to Hedstrom with a proposition—turning Hedstrom’s motor-driven scoots into mass-produced vehicles for the general public. By January of 1901, the two had an agreement in place, and in May of that same year the two partners introduced their first prototype to the world. Two more prototypes followed before Indian went into full production. Indian produced 143 bikes in 1902.

Hedstrom’s first Indian motor was an 18-inch single-cylinder mill based on the De Dion engine with which he was so familiar. It was a four-stroker with the intake valve mounted above the exhaust valve in a pocket to one side of the combustion chamber. Hedstrom used as few moving parts as he could, reasoning that the simpler the motor, the less that could go wrong and the more reliable it would be. You can see evidence of that in the first Indian’s breathing arrangement. A spring held the intake valve in its seat so that it was sucked open as the piston moved downward on its intake stroke. The exhaust valve was actuated mechanically by a single cam.

Those first motors were made by Aurora Automatic Machinery in Illinois, but by 1907 Indian had its own larger factory making the motors and bikes up and running in Springfield, Massachusetts. This was also the year Indian launched its first V-twin. An outgrowth of Hedstrom’s F-head single cylinder, the 42-degree vertical twin made Indian a heavy hitter at the racetrack as well as salesroom floor. Indian took first, second, and third place honors at the 1911 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT), becoming the only American manufacturer to do so.

With that kind of success under its belt, you can see why Indian grew so big that by the mid-1910s it was producing 30,000 models a year. It was the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, with more than 3,000 dealerships and a factory in Toronto. Business wasn’t perfect, however.

Hedstrom and Hendee both left Indian during this time. Hedstrom resigned from the Indian Motorcycle Company on March 24, 1913, after a disagreement with the board regarding dubious practices to inflate the company’s stock values. Hendee resigned in 1916, at the age of 49, after a disagreement with the board of directors over the direction in which the company was heading.

Despite these setbacks Indian was still a powerhouse, though two new challenges forced them to adapt to changing times. Namely, evolving competition and Henry Ford. While Hedstrom’s motors were great for motorized bicycles, new frames made to hold more powerful, true motorcycle motors threatened to leave Indian in their dust. Meanwhile, Ford’s release of the Model T completely redefined the entire market for cheap, reliable motor-driven transportation in America. These two factors faced Hedstrom successor and Indian chief engineer Charles Gustafson. Indian needed a stronger powerplant to keep up with Harley and its other competitors while keeping costs down in the face of mass-produced, affordable automobiles.

Enter the 61-inch Powerplus side-valve V-twin. Introduced in 1916, the Powerplus’ valves had their stems at the bottom and heads at the top. This let Indian use a simple camshaft to actuate the valves and keep costs down. The Powerplus was Indian’s dominant design at this time and also had its influence on the company’s racing program.

Racing was such a big part of getting the word out to prospective motorcycle buyers that all the big companies at the time had their own racing R&D making exotic track machines. While the sport advanced motorcycle technology in much the same way the Space Race advanced aerospace and other techs in the 1960s to 1980s, it was very expensive. More and more companies turned to their streetbikes as the basis for their racers in order to keep costs down.

Indian’s point man for that was Irishman Charles Franklin. He’d ridden an Indian to a second-place finish at the Isle of Man in 1911, worked at an Indian distributorship, and finally came to work at the engineering department at the Wigwam in 1916. Franklin knew his way around a motor as well as he knew his way around a racetrack. His experiments on his Hedstrom racers led to the discovery of the squish principle by which the combustion chamber is reshaped for better airflow. When he got his mitts on Indian’s Powerplus side-valve motor, he turned it into one of the baddest machines at the track. Indian’s biggest rival, Harley-Davidson, felt so threatened by Franklin’s Powerplus-equipped racebikes that it dropped its eight-valve designs and focused on side-valve motors of its own.

The year 1920 was so great for Indian racing that it can only be described as historic. Gene Walker set a string of land-speed records at Daytona Beach for Indian that year, and Albert “Shrimp” Davis rode his Powerplus Indian to victory at a race averaging more than 100 mph—the first time a motorcycle had ever done that.

This was also the year Indian introduced one of its finest motors ever—the 37-inch, Franklin-designed Scout. Much like Harley’s Knuckle is the basis for its Big Twins, the Franklin’s Scout was the OG version of every Indian motor that followed until 1953 (except the Four). Indian enlarged the Scout to 61 inches in 1922 for the Chief, made a 74-inch version for the Big Chief, and produced a 750cc race version in 1927. The powerplant was so strong and adaptable that its racing legacy continued all the way into the 1950s.

Its influence might have been even greater if it weren’t for the idiots in charge of the company. Maybe if the board of directors hadn’t pushed Hendstrom and Hendee out years before, Indian would’ve enjoyed the same unified guidance and focus that steered Harley-Davidson to prominence. Instead, the bosses put a lot of effort into building things it knew nothing about, like motorboats. Those failed ventures pissed away the vital funds Indian would later need to weather the Great Depression.

By 1930, Harley had devoured Indian’s market share. E. Paul DuPont took command of Indian and tried to bring focus back to making great bikes. Not only was he a good judge of people and a very successful businessman, but DuPont was also an avid and knowledgeable motorcycle enthusiast. He’d have been the perfect doctor to save Indian if his patient had been just a tad healthier. But it wasn’t.

The DuPont team was forced to make cost-cutting measures to keep Indian’s doors open to the point that little was left for technological innovation. Harley-Davidson didn’t have that problem. While H-D was building the new Knucklehead motor and cementing its place in American motorcycle history, Indian focused on styling just to stay afloat.

Tech advancements were few and far between for Indian in the 1930s, but an earlier purchase lead to one of the most iconic motorcycles Indian produced during that time—the Indian Four. Purchased by Indian in 1927, Ace Motorcycles made a sweet, elegant four-cylinder motorcycle that became the Indian Four. Production was moved to Springfield, and the motorcycle was marketed as the Indian Ace.

In 1928, the Ace was replaced by the Indian 401, a development of the Ace designed by Arthur O. Lemon, former chief engineer at Ace who was employed by Indian when they bought the company. The Ace’s leading-link forks and central coil spring were replaced by Indian’s trailing-link forks and quarter-elliptic leaf spring.

By 1929, the Indian 402 would have a stronger twin-downtube frame based on that of the 101 Scout and a sturdier five-bearing crankshaft than the Ace, which had a three-bearing crankshaft. Despite the low demand for luxury motorcycles during the Great Depression, Indian not only continued production of the Four but continued to improve upon it. One of the less popular versions of the Four was the “upside-down” engine on the 1936–1937 models. While earlier (and later) Fours had inlet-over-exhaust (IOE) cylinder heads with overhead inlet valves and side exhaust valves, the 1936–1937 Indian Four had a unique EOI cylinder head, with the positions reversed. In theory, this would improve fuel vaporization, and the new engine was more powerful. However, the new system made the cylinder head, and the rider’s inseam, very hot. This, along with an exhaust valve train that required frequent adjustment, caused sales to drop at a time when Indian couldn’t afford to lose any more money.

Indian offered dual carbs on the Four in 1937 and even reverted the motor to its pre-1936 version in 1938, but those efforts failed to revive interest in the bike. The Indian Four was discontinued in 1942, but it was not forgotten. Its historical significance got a nod in 2006, featured as part of a four-panel stamp series named “American Motorcycles.”

The 1930s were brutal for Indian, and the ’40s weren’t any kinder. Forced to compete with Harley’s Knuckle-powered twins for military contracts, Indian’s outdated side-valve iron couldn’t land the lucrative government orders that brought other American companies out of the Great Depression and back into profitability. By the war’s end, Indian had 400 dealerships nationwide and was only selling 2,000 bikes a year.

DuPont sold the company to a financial group headed by Ralph B. Rogers the same year the war ended. He was a 36-year-old businessman with a proven record of successes. He saw the demand for lighter-weight motorcycles in the post-war era and wanted Indian to lead the way in capitalizing on it. Indian discontinued the Scout and started manufacturing lightweight motorcycles like the 149 Arrow, the Super Scout 249, and the 250 Warrior, introduced in 1950. Production of traditional Indians dropped off drastically.

Rogers bought The Torque Manufacturing Company to get the light motor he wanted for Indian. Torque had been working on a new bike engine design since the 1940s. Made from the latest alloys and technology, Torque’s motor promised to be more efficient and weigh less than competing offerings.

Torque might have even saved Indian’s life if the company had enough time to work out the kinks. Indian’s finances dictated otherwise, however, and the renamed Dyan-Torque was rushed into production in Indian’s new lightweights. The results were disastrous. Mismatched cam gears, damaged bearings, and a crappy oil system with a penchant for failure doomed bike sales. The company ended production of true Indians in 1953. Although the brand stuck around for a while after that, it was merely an attachment placed on foreign bikes to make them more palatable to American consumers.

There’ve been no fewer than three failed attempts to bring Indian back with its own American-made iron. All of them missed the object lesson handed down from the 1940s and ’50s—style alone isn’t enough. Polaris dodged that bullet because it understands what made Indian great: an awesome motor with its own style and technology—not some Harley knockoff. It’s way too early to tell what will happen to the brand at this point, but so far it looks like Polaris is off to a much better start because it understands and honors Indian’s rich heritage.

Hendee and Hedstrom, 1902.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

The first post-war lineup consisted only of the Indian Chief as design and production were ramped up for consumer models after being focused on military bikes during the war.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

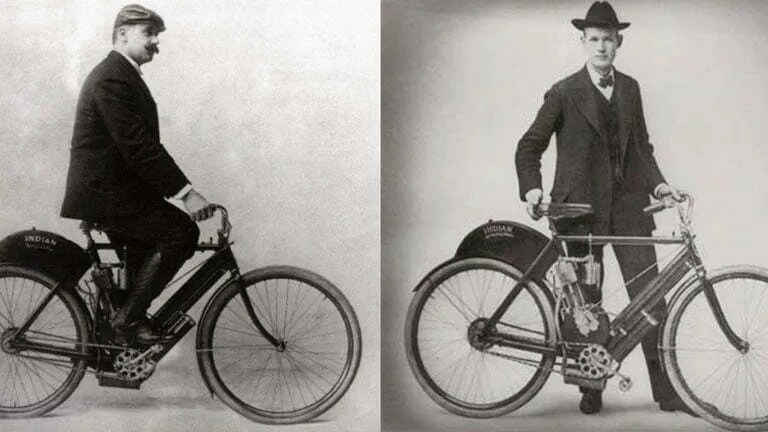

Burt Munro chasing world record glory on the salt aboard his Indian Scout.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

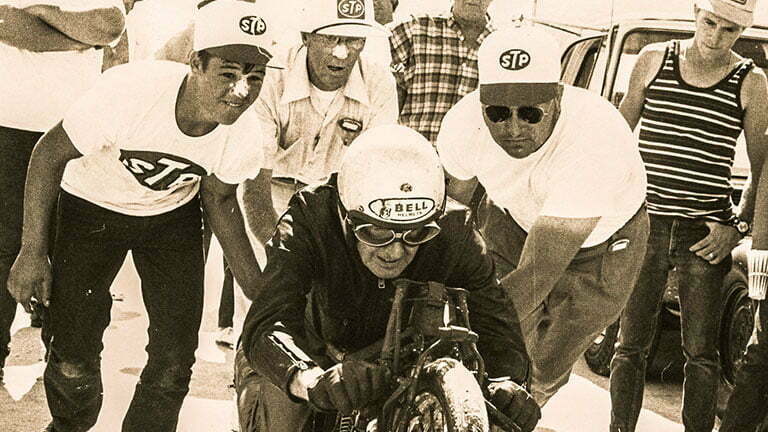

Artist David Uhl’s Spirit of Sturgis depicts rally founder Pappy Hoel, who owned an Indian dealership in Sturgis.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

Racer and bike builder Roland Sands brings Indian back to the dirt track for the Hooligan series.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company

2016 Indian Roadmaster.

Courtesy of Indian Motorcycle Company